Native image lazy-loading: how a single HTML attribute decreased initial load times by 40%

July 15, 2020

4 min read

According to HTTPArchive, images are the heaviest and most requested asset type for most websites. In a lot of cases, users download many below-the-fold images before they start interacting with the page, leading to slower load times, and higher bandwidth and memory usage.

Image lazy loading is a new browser feature that lets you skip

downloading off-screen images until the user scrolls near them. All by

adding a single attribute loading="lazy" to your <img> elements.

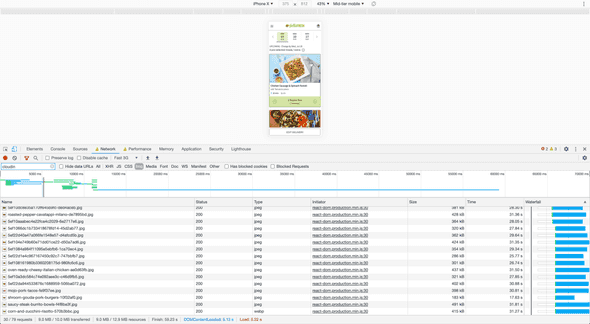

<img src="image.png" loading="lazy" />At HelloFresh, we offer our users a weekly selection of recipes to choose from. As we expand our offering, more and more recipes are added to the menu page, reaching 40+ recipes in some cases. This led to users having to download a lot of images, even if they never get to see them, making menu expansion inversely correlated with user experience.

Consequently, image lazy loading seemed perfect for our use case. So we went ahead and added the loading="lazy" to our recipe card

components, then did a benchmark to compare the results on our initial

load times, which were

the following:

The numbers

Note: These numbers measure the initial page load, before any user interactions.

Without lazy loading

- 30 recipe image requests

- for a total of 9MB

- taking 60 seconds to finish initial resource downloading

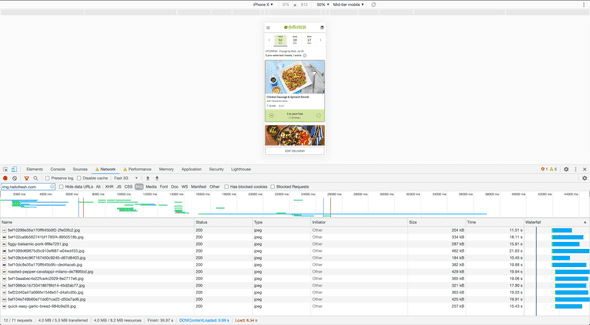

With lazy loading

- 12 recipe image requests (60% decrease)

- for a total of 4MB (56% decrease)

- taking 36 seconds to finish initial resource downloading (40% decrease)

As you can see, the effect is quite significant, and gets more and more magnified the more images you add to your web page.

Trade offs

Lazy loading can drastically improve initial page load time, in other words, reducing the time it takes for something in the page to be interactive.

However, of course, as with everything, nothing comes for free. The caveat here is that if the user’s internet connection is slow, they’ll scroll down to see the other recipes, only to find empty images that they still would need to wait for to be downloaded.

And some users would prefer to let the page take its time to download its content at one go, and to be fully interactive afterwards. One example is when you load the page on a fast connection, then go somewhere with a patchy connection (such as underground trains), only to scroll down and find that a big part of the page is still not fully downloaded or interactive.

However, this is the trade-off you get with deferred loading and code splitting in general, so it’s not specific to this particular attribute.

In our case, we thought that even if in some edge cases the user experience could be degraded, for most users the experience would be substantially faster and less resource intensive, making the trade-off worth it overall.

Browser support

Image Lazy loading is currently supported by Chrome, Edge, Firefox, and Opera. It is backwards compatible, so if the browser doesn’t support it, it will just fall back to the default “eager” loading behavior. You can also add a polyfill if you wish to support other browsers.

Conclusion

In many cases, improvements in web performance require sophisticated solutions by experienced engineers, which makes them harder to adopt in most websites.

It’s quite rare to reap such impressive performance gains by adding a single (backwards compatible) line of code. The return you can get for such low investment makes image lazy loading one of the best low-hanging fruits when it comes to improving web performance.

If your website loads multiple below-the-fold images, and you’re looking for an easy performance gain, I would highly recommend taking a look at image lazy loading. It’s just one attribute, that’s baked into the browser, backwards-compatible, and SEO-friendly.

For more technical details about how native lazy loading works, I recommend checking out this article.

Written by Mohamed Oun, a software engineer in Berlin. You can follow him on Twitter.